With ghosts and witches and talking animals folk tales step from the adults’ porch or parlor into the nursery. Although children’s folk and fairy tales are typically told for amusement during leisure hours, one occasionally hears of their being used, like songs, to accompany the labor of many hands and, like the hands, make like work.

With ghosts and witches and talking animals folk tales step from the adults’ porch or parlor into the nursery. Although children’s folk and fairy tales are typically told for amusement during leisure hours, one occasionally hears of their being used, like songs, to accompany the labor of many hands and, like the hands, make like work.

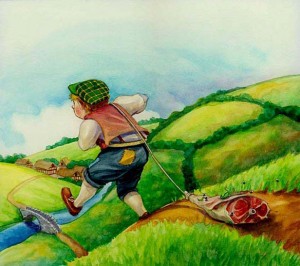

The North Carolina versions of the Jack tales have still another practical relation to Southern life. In their portrayal of Jack as a typical easy going, unpretentious mountain boy as well as in their use of the mountain vernacular, the Jack tales are excellent examples of the adaptation of the Old World folk tales to Southern settings and folkways, a kin to the democratization and localization of British ballads.

In the Jack tales, too, knight-errantry and chivalry survive on a democratic and popular level. The persistent appeal of the Jack tales to the Southern folk rests not simply on their appeal to children but also on the appeal of the ever triumphant Jack as a symbol of the bottom rail on top. As a trickster hero who overcomes through quick wit and cunning rather than by physical force, Jack belongs with Brer Rabbit and Old John. Symbolic of the dreams, desires, ambitions and experiences of the heads of these little fellers may touch the clouds.